From sustaining the American Revolution to the Underground Railroad – here are 4 Black Chefs that shaped American history.

There’s this incredible book called At The Table of Power: Food and Cuisine in the African American Struggle for Freedom, Justice, and Equality. It was written by Diane M. Spivey, a culinary historian who has studied and recorded African American food traditions and cooking for several decades now.

In the prologue, the author says, “the foundation of America’s national cuisine was formulated in the pots and cauldrons of America’s southern Black cooks.”

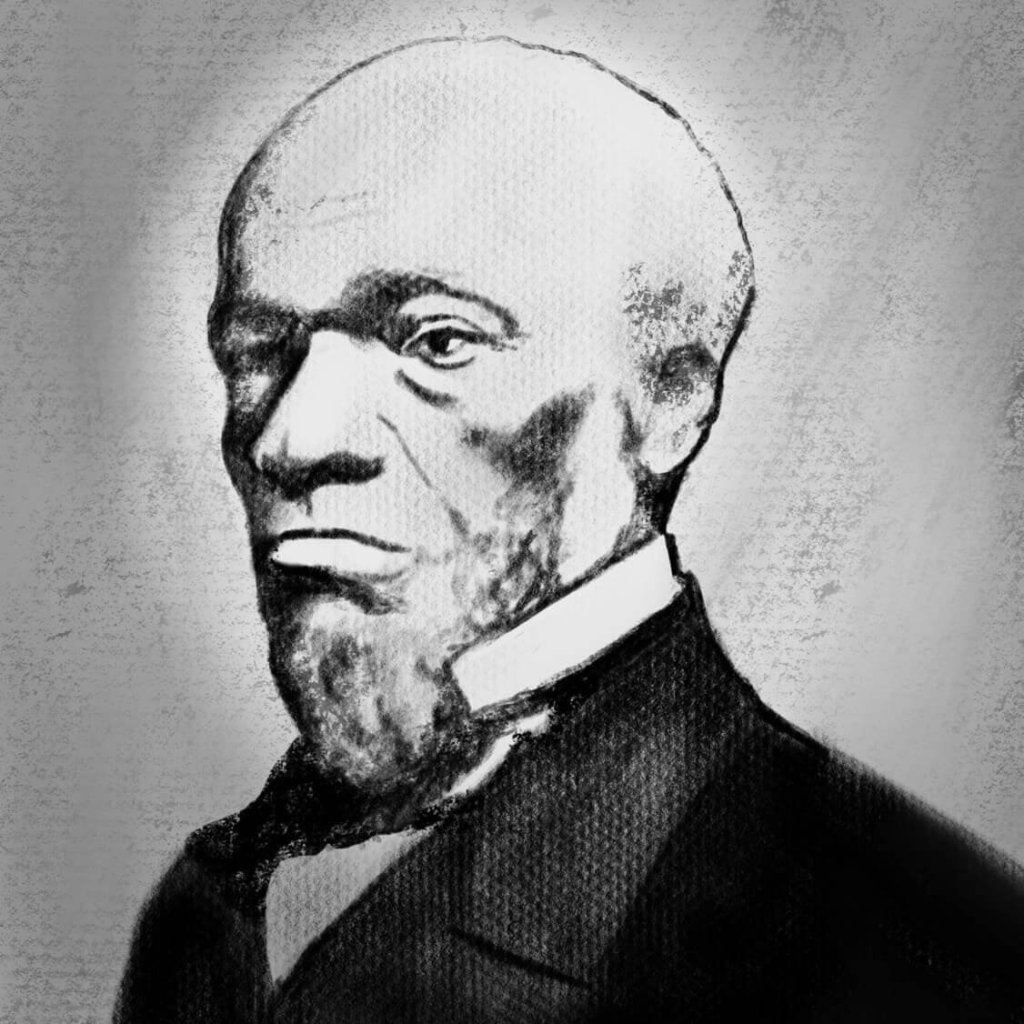

Cyrus Bustill

There are many examples of Black chefs contributing to the American Revolution. One of them was Cyrus Bustill of New Jersey. Bustill was born to an enslaved African mother and a white Quaker father. When his master died in 1762, the plan was to sell Bustill’s services for a number of years. Bustill, who despised slavery, took this opportunity to take control of his own life. He sought out the Quaker Thomas Prior, and worked for him for seven years before becoming a free man.

Prior was a baker, and Bustill learned to read and developed his own methods of bread baking. He later established his own bake shop, which became successful as many prominent families sent flour to his shop to be turned into baked goods.

He sold bread, cakes, and biscuits for profit for years, and with the outbreak of the American Revolution, he became a supplier for the American forces in his area. Contractor for the troops, Thomas Falconer, issued a certificate saying Bustill was employed in the baking of all the flour used at the Port of Burlington, and on the back of the certificate confirmed that Cyrus Bustill had baked all the bread for the Troops at this Port (of Burlington) in the month of May.

Robert Bogle

Let’s move on to 19th century Philadelphia and catering.

In the final decade of the 1700s, Philadelphia was the capital. Even when the capital moved, Philadelphia remained a financial hub. There were working French chefs in the city, however the supply of experienced chefs compared to the demand opened opportunities.

Robert Bogle was born into slavery in Philadelphia in 1775.

He began his employment as a waiter, before developing the idea that those who wished to entertain from their homes would find great convenience in having him purchase, prepare, and serve the entire meal in their homes with his staff.

Turning the cooking and domestic service into an organized business, Bogle is widely credited with being the creator and founder of catering in the United States. W.E.B Du Bois noted that Bogle set the fashion of the era, and no event was considered properly presented unless presented by Bogle.

Bogle had a large roster of wealthy White clientele including Nicholas Biddle, the president of the Bank of the United States. So impressed by Bogle’s services, Biddle composed ‘An Ode to Bogle’.

In this ode, there is a passage –

“Meta, thy riper years may know

More of this world’s fantastic show;

In thy time, as in mine, shall be

Burials and poundcake, beaux and tea;

Rooms shall be hot, and ices cold,

And flirts be both, as ‘twas of old;

Love too, and mint-stick shall be made;

Some dearly bought, some lightly weighed;

As true the hearts, the forms as fair;

And equal joy and beauty there;

That smile as bright and soft the ogle;

But never – never such a Bogle!”

Peter Augustin (& the Augustin-Baptise Family)

Bogle’s place in the catering ranks was taken by Pierre – Peter – Augustin after 1836, and it was said Bogle helped the Augustins set up business.

Peter Augustin was a Haitian biracial chef – his wife whom he married soon after arrival in the United States – could not bear their children being born into a slave state so they moved to Philadelphia.

In their earlier years in Philadelphia, Augustin was listed as a barber and hairdresser, and he later established himself as a confectioner. Catering became his primary business, and it became a legendary business at that. The Augustins built a catering empire that shaped the American catering industry – the wealthiest families of the city and foreign diplomats were served by Mr. Augustin and his fame was worldwide.

They did both solo affairs and collaborations – the 1824 Banquet for General Lafayette when he visited for his American tour – was overseen by the Augustins but most of the food was prepared by Parkinson Caterers.

The Augustins were also hired for a dinner for Grand Duke Alexis in 1871, as well as a huge banquet for General Ulysses S. Grant.

Aside from delighting clientele at catering parties and other functions, they also served the public at their restaurant.

Private dinner parties continued to hire the Augustin experience even after Mr. Augustin’s death. His widow, Mary F. Augustin continued the business with one of their sons, and it became Mary F. And Son. Theodore Augustin wed a daughter of another famous catering family, the Baptises, and then the businesses merged into the Augustin-Baptise catering firm.

Aunt Clara, as that Baptise daughter became known, was clever and stern, while also humorous, witty, and engaging. She had a generous heart, and while her brother was the businessman, he discussed all negotiations, suggestions, and arrangements with Clara Augustin. Following the death of their mother, it was Clara Augustin that ran the business.

Thomas Downing

Now, food wasn’t just a means to economic freedom. Let’s talk about New York, oysters, and the Underground Railroad.

Thomas Downing was born in Virginia in 1791. His family was freed by Captain John Downing, a Methodist. Along with his chores, Downing grew up fishing. He raked for oysters and clams as well. In 1812, Downing went North along with the troops – he learned how to prepare terrapin at the Joe Head House. Years later, New York’s Astor House held a competition of stewed terrapin preparations. Downing was awarded and headed to New York City armed with an expertise on oysters, clams, and terrapin. He was determined to enter the business of preparing and serving food.

Following some local networking via letter of introduction, Downing found employment at Bunker House on Broadway. Shortly after, he opened his business on 5 Broad Street.

Downing studied oysters diligently, and his business bloomed from his expertise. It was enlarged to include 3, 5, and 7 Broad Street.

The demand for oysters meant high competition. Downing would wait by the dock at midnight when his competitors slept at home. He would bargain with the captain, and assisted the captain in selling the less desirable oysters. Sometimes he would bargain the entire cargo, forcing his competitors to plead before him.

He was said to be a favorite with the captains, as he paid them well and treated them generously when they came to his house.

His place became the place to be. His reputation travelled to Europe, where Lord Morpeth, Charles Dickens and other well-known foreigners visited his establishment to try his fried oysters. In 1847, Downing prepared and shipped a barrel of pickled oysters to Queen Victoria. The Queen responded to his gift, as she had delivered to him a gold chronometer with her initials.

Through his food, Downing became very well connected, including the extension of the Erie Railroad to Dunkirk.

Despite his fame, he was very humble, once issuing a correction regarding a dinner he had been mistakenly credited for.

As Downing was a prominent choice for public functions, and had caught the interest of Charles Dickens, he was asked to cater The Boz Ball held on Valentine’s Day in 1842 to honor Charles Dickens and his wife who had come to the States.

Thousands of guests showed up, including ex-mayor Philip Hone, friend of John Jacob Astor, as well as Presidents John Quincy Adams and Martin Van Buren.

Despite his connections, Downing, the “great man of many oysters” became a target for people who loved food prepared by African people but hated Africans. For example attorney George Strong made several references to dining at Downing’s oyster house yet was also ardently racist and opposed to abolition.

Furthermore, Downing offered The New York Herald a hefty loan to survive bank panic, yet several years later, while under different leadership, the paper said that Downing better stick to his oysters and leave politics alone.

Like many Black chefs, including free men, Downing was lauded for his talents yet this did not protect him from hostility and discrimination.

Up until the passage of Charles Sumner’s Civil Rights Act of 1875, Black New Yorkers lived under “Jim Crow” type conditions. Thomas Downing, one of the wealthiest Black business owners in New York, patronized by the White elite, including the president of the Harlem Railroad, was beaten by agents of the Harlem Railroad.

Philip Hone, one of Downing’s biggest culinary fans and mentioned early as a guest at The Boz Ball Downing served, attended a meeting on August 27, 1835, which in his own words, “opposed the incendiary proceedings of abolitionists”.

In many ways, the free Black folk shared with their enslaved brethren the common struggles. Thomas Downing’s oyster house was said to be the New York City headquarters for the Underground railroad. Hundreds of fugitive enslaved folk were clothed and fed on their way to Canada, where slavery was abolished decades earlier than the US as part of the British Parliament’s Slavery Abolition Act of 1833.

Sources:

SPIVEY, DIANE M. At the Table of Power: Food and Cuisine in the African American Struggle for Freedom, Justice, and Equality. University of Pittsburgh Press, 2022. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv2z862gr. Accessed 12 Apr. 2025.

For more food history, stay tuned!