There are six commonly acknowledged cradles of civilization. One of them was Mesopotamia, the earliest known civilization which was founded on the land between rivers.

Neolithic comes from the Greek words neos, and lithos. Neos means new, and lithos means stone. The New Stone Age was named for the changing of stone tools. It also marked the early domestication of animals and plants, in an arc of sites that would become known as the Fertile Crescent.

Agriculture with domesticated plants and animals developed there by 8500 BCE. They had cattle including sheep, goats, and pigs. Crops included barely, lentils, peas, chickpeas, and broad beans. Fruits including figs, grapes, olives, and dates appeared between 6500 and 3500 BCE.

By 6500 BCE, Fertile Crescent farmers were using earthenware pottery. Earthenware pots and strainers could be used to make milk products such as yoghurt, ghee, or cheese. Pots were also easier to manufacture than stone vessels, making porridge or gruel more accessible for mothers to feed infants.

Fertile Crescent villagers also used the loom around this time, weaving textiles from spun flax fiber and eventually, sheep’s wool. Forging metals was introduced, but would not become a major factor in human societies until a later era.

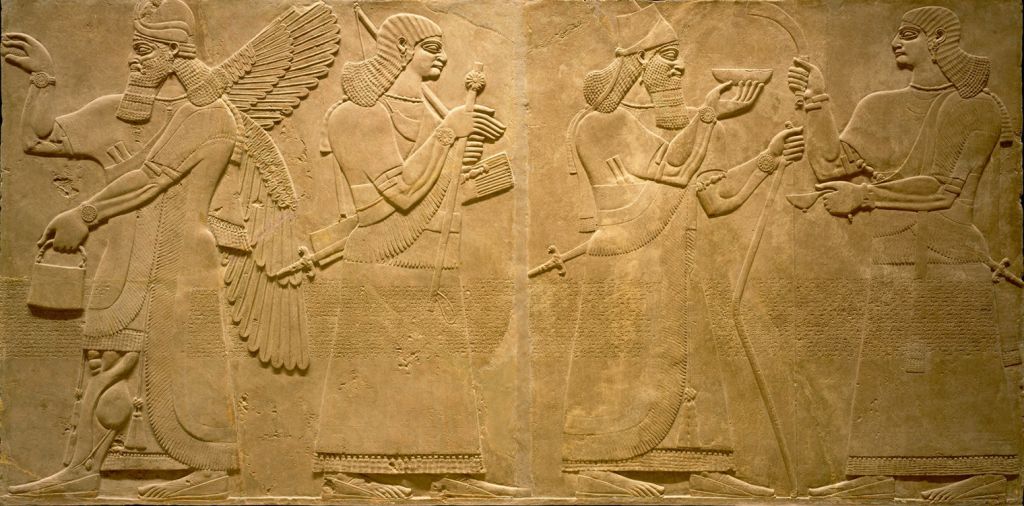

Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia is a region within the Fertile Crescent, is critical to human history. It is the site of some of the most important developments in human history. Historically, it includes modern day Iraq, and parts of modern day Turkey, Syria, and Kuwait.

There are four main environmental zones in Greater Mesopotamia.

- In Central Iran, there is an interior drainage basin. The basin is filled with desert soils, including sierozem, and is overspread in some places by shallow lakes surrounded by flatland. There are rugged mountains, some of which are ore bearing, including copper and turquoise. There were animals like gazelle that would have been hunted, but there was a lack of options for irrigation. Still, there appear to have been some settlements, especially near copper sources.

- The Zagros Mountains descend in tiers toward the Tigris-Euphrates basin. These porous mountains can trap great quantities of water from snow and rain, releasing it through springs. These springs would then feed the streams. There are alluvium rich valleys, where summers are warm and dry, and the winters are cool and wet. The hillsides have a variety of vegetation, and well-irrigated slopes grow hard-grained annual grasses including wild emmer wheat, barley, and oats.

- In the Assyrian steppe region, there are plains with soils of high fertility. Mountain streams form into larger rivers such as the Tigris, Karkheh, Diz, and Karun. This allows for wide floodplains which are good for farming. While hot and dry in the summer, winter rain transforms the region into meadows of grasses such as Bermuda, canary, and wild narcissus. Gazelle, wild ass, and wild cattle once roamed, and the rivers had carp and catfish. The Assyrian steppe was also rich with oil, and traded bitumen and wild asphalt used for tool making. Other areas were breadbaskets for winter wheat.

- Southern Mesopotamia was impacted by the lower drainage of the Tigris, Euphrates, and Karun flowing together as they emptied into the Persian gulf. There are two biotypes: an alluvial desert on the higher ground and reed bordered swamps in lower-lying areas. The delta is a subsiding geosyncline; a long, narrow depression in the Earth’s crust that fills with sediment over millions of years. In the case of Southern Mesopotamia, it filled with river alluvium, which yields rich and fertile soils. In this zone, urban life, civilization, writing blossomed.

Prior to agriculture, archaeological remains indicate collecting, hunting, and gathering. Some members of early Mesopotamia collected snails, turtles, crabs, clams, and seeds. Other members hunted and fished; caves included remains of fish, birds, and small mammals. However, a more significant portion of the meat diet came from animals such as wild sheep, goat, ox, pig, wild ass, gazelle, and deer.

In 1963, a collection of around 10,000 carbonized seeds was found at Ali Kosh, an archaeological site located in west Iran. The area is considered part of the Assyrian steppe, and nearby is range of wild wheat and barley. However, local plants such as alfalfa, wild legumes, and wild capers, were also collected.

Other plants beneficial to collectors would be ryegrass, wild flax, and large-seeded wild legumes such as lentils, chickpeas, and vetch. The lowlands had dates, and the foothills had acorns, almonds, and pistachios. In the northern mountains, there were grapes, apples, and pears.

In the late pre-agricultural period, there was trading of obsidian from its source in central and eastern Turkey to caves in central Zagros. Natural asphalt was traded in the opposite direction, from the tar pits of the Assyrian steppe to the mountains. This indicated early practices of moving commodities from various zones.

The ancient histories of Mesopotamian agriculture are investigated through the material remains, including seeds, granaries, storage pits, and tools. There are also passages within the law codes of the Sumerians, Old Babylonians, and Assyrians. Most remarkably, there was a farmer’s almanac of sorts used by the Sumerians just before the era of Hammurabi.

Ur was an important Sumerian city-state in ancient Mesopotamia; principal field crops mentioned in Ur III are barley, wheat, emmer, sesame, onions, peas, and beans. Dates, pomegranates, and figs feature on the lists of products coming from smaller plots, which are gardens.

Of the many texts from Ur III, few mention wheat or emmer, in comparison to the many that mention barley. Barley fed both humans and animals, and dates were also important. Aside from playing a major role in the ancient Sumerian diet, the wood of date palm was important considering there were not many other trees.

Sumerian fields were survey constantly, and classified based on their conditions. Perhaps the field was good, hard to work, irrigated or too high for irrigation. First preparation of the fields usually began right after the June harvest, before the summer became too hot and dry. In late September and October, larger fields were plowed and smaller plots were prepared with picks and spades.

After the grain was harvested, the grain had to be moved to a place of storage. Umma was another ancient city in Sumer. A tablet from the city records that 18 men spent three days to load about 1,500 bushels of barley onto a ship. Over the course of another four days, the ship was rowed to a granary in Umma. An additional four days were spent unloading the barley and putting the cargo into the granary.

The question of how humans first transitioned from village life to urban life has fascinated researchers for many years. The transition was long thought to have first happened sometime around 4000 BCE, in what many archaeologists call the Uruk phase. Uruk is an ancient city located in modern day Iraq, east of the current bed of the Euphrates river.

However, archaeologists have found regional evidence of urban revolution in the previous period, called the Ubaid. The Ubaid was estimated to have lasted between 5500 BCE until about 4000 BCE.

According to University of Chicago archaeologist Gil Stein in 2012, the Ubaid is key to understanding the roots of the urban revolution.

A handful of sites investigated by archaeologists indicates that a loose network of local peoples in the region helped shape the way of life which led to cities. It is widely agreed that irrigation and trade were key factors. Questions remained whether the exchanging of ideas happened between independent peoples, or a dominant group asserting control.

Sumer is the name of ancient Southern Mesopotamia; here archaeologists discovered the oldest cities. Among the oldest and largest within those early cities was Uruk.

The people of this era were among the first to spin wool into cloth, create intricate pottery, irrigate their fields, and live in well planned houses with multiple rooms. Archaeologists also found evidence of early class systems; there were some infant graves with an abundance of goods. East of Baghdad, there was a home several times as large as the town’s smallest dwelling.

Although southern Mesopotamia was rich with soil, they lacked other natural resources such as timber and metals.

In Northern Mesopotamia, Tell Zeidan is located in what is now modern day northern Syria. It is made up of three large mounds.

Elaborate seals marked goods, and rooms reveal some people had control over goods or access. This indicates early administrative systems, and potentially the start of hierarchy. The people processed copper and crafted obsidian tools, using raw materials from Anatolia. Anatolia, also known as Asia Minor, makes up the majority of the land in modern day Turkey.

The people of Tell Zeidan used bitumen from Iraq to make sickles for harvesting their grain. Bitumen is a black, sticky substance, often referred to as asphalt or tar in modern English. It is derived from crude oil.

A variety of archaeological finds indicates that the Ubaid was not a monolithic culture; according to archaeologist Guilermo Algaze, the Ubaid is actually many Ubaids. They developed in tandem, exchanged goods and ideas, and possibly competed with each other.

According to Algaze, this indicates the advancement of social complexity among humans.

In the early 2000s, archaeologist Robert Carter co-led a team to find the oldest known seafaring boat while excavating an Ubaid encampment on the coast of Kuwait. Since then, more teams dug up a 200 by 50 meter area, discovering six to eight rectangular buildings. The architecture of the building strongly matches that of the Ubaid architecture.

A large room with a stone podium was originally thought to be a temple. However, the discovery of beads, shells, and flint drills led to the conclusion that this was a workshop.

By 4000 BCE, Ubaid pottery and other materials started to fade from the record. Within a century or two, the protocities of Uruk in the south began to expand. In the north, it was Tell Brak. They dominated surrounding areas, and employed administrators and craftspeople.

The Ubaid introduced a new style of housing, trade expansion, specialty jobs, temples, and growing acceptance and development of social hierarchy.

This is a mere intro to the fascinating world of ancient Mesopotamia. To learn more about key groups such as the Assyrians and Babylonians, stay tuned!

Subscribe for free to never miss an article!

Sources:

BELLWOOD, PETER. “The Fertile Crescent and Western Eurasia.” The Five-Million-Year Odyssey: The Human Journey from Ape to Agriculture, Princeton University Press, 2022, pp. 220–50. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv28sc829.13. Accessed 12 Apr. 2025.

CLINE, ERIC H., and Glynnis Fawkes. “FIRST FARMERS IN THE FERTILE CRESCENT.” Three Stones Make a Wall: The Story of Archaeology, Princeton University Press, 2017, pp. 115–28. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvc77gc5.13. Accessed 12 Apr. 2025.

Flannery, Kent V. “The Ecology of Early Food Production in Mesopotamia.” Science, vol. 147, no. 3663, 1965, pp. 1247–56. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1715610. Accessed 13 Apr. 2025.

Jones, Tom B. “Ancient Mesopotamian Agriculture.” Agricultural History, vol. 26, no. 2, 1952, pp. 46–51. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3740087. Accessed 13 Apr. 2025.

LAWLER, ANDREW. “Uncovering Civilization’s Roots.” Science, vol. 335, no. 6070, 2012, pp. 790–93. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41487256. Accessed 13, Apr. 2025